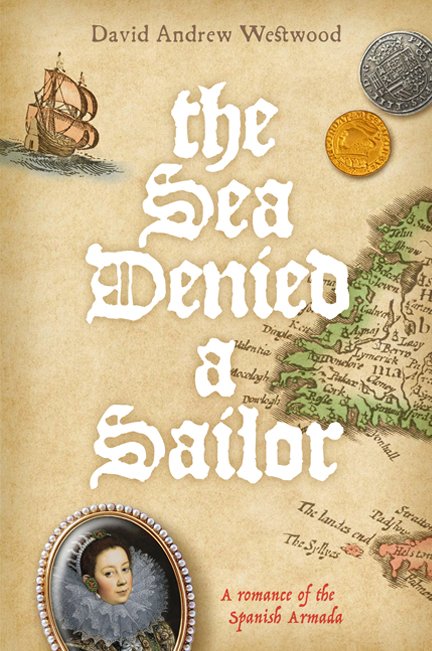

THE SEA DENIED A SAILOR

Young love, and an epic chase from England, Ireland, and Spain all the way to Peru.

In 1588 Philip II, the King of Spain, funded by Pope Sixtus V, decided to invade England to bring her back to the “true religion.” To this end he assembled 130 ships and thousands of men to sail from Lisbon north.

The English navy prepared to challenge this fleet, but in the end it was the weather that defeated the Spanish. After battles in the English Channel, the ragged remnants of the Armada struggled up and around the British Isles only to meet more storms off the western coast of Ireland. By this time they had been at sea for months, and their crews were racked with disease and starving. Many of their ships were either pushed aground on the rocky shore, or landed purposely to seek help from the Catholic Irish. Only 60 ships made it back to Spain, and those half-empty. Since no troops set foot on English soil, the Pope never paid up.

Review

“Everyone has heard of the Spanish Armada’s defeat. Here is another highly readable historical novel by Westwood that follows a stowaway with surprising backstory, who washes onto the coast of Ireland. Dynasties clash as love cross-pollinates at the birth of a new empire.”

—Gaoler, Amazon reader

Sample chapter: © David Andrew Westwood 2022, all rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced without written permission from the author.

Scene 5:

I Re-evaluate the Irish, and Form a Brief Friendship.

Compared to my father’s untimely death, and the clash of mighty navies off the southern coast of England, our local concerns seemed of little consequence. But my petty duties continued still.

There had been instances of hedgebreaking at the house, the stealing of firewood. Then poachers were seen running off with a few hens and piglets. Three of us chased them into a village a few miles away. As we rode through, a hail of stones pelted us from either side of the lane, and one of my men fell unconscious from a blow to the temple. I had to strap him across my horse and return for reinforcements. Once again I approached the settlement, this time with more men, and more warily.

I called out to warn the villagers that if they gave up the poachers they would be spared, but if they did not, all would be captured and imprisoned. But they either did not understand my English speech or pretended not to. We were invaders to them, after all, and I was an enemy, just as the Spanish were enemies to me. To feign ignorance is, I suppose, one of the weapons of the otherwise unarmed.

My duty was clear. But first I attempted to enlist the help of someone who might have some power o’er them. There was no chieftain here in this land’s poor corner; not e’en a blacksmith; but there was a church, and inside likely a priest. When I left my men left outside as guards and entered, I was surprised to see that e’en ’mongst such poverty, its house of worship glowed with rich appointments – chalices, crucifixes and, for the illiterate, bright frescoes and tapestries depicting Bible scenes. There was also a rood screen with crucifix to separate the chancel from the nave, which had been banned as idolatrous in Protestant churches.

The priest came forward at my entry. I was not sure if genuflection had also been prohibited, so I merely gave him a short bow of respect, and introduced myself.

“My name is Father Twomey,” he replied. “I would prefer your sword remain outside, sir.”

I was glad we spake the same tongue. He had likely attended divinity school in England during Mary’s reign. “My sword stays at my side in Ireland, Father. ’Tis a necessary precaution, gi’en the propensities of your flock.”

He smiled. “My flock have no wish to be servants of your queen, since they get none of her benefits but all of her ire.”

Though I saw his point, we remained on opposing sides. “I have no say in Crown policies," I told him. “I am myself but a servant of the monarch, and follow her orders. The villagers have been stealing the lord’s property, and I am to either return it or punish them.”

“You are to punish the poor for their poverty?”

I liked not this chop-logic. “Does not the Bible say, ‘thou shalt not steal’?”

He conceded this with a nod. “But it also says, in Proverbs, ‘Men do not despise a thief when he stealeth to satisfy his soul, because he is hungry’.”

Despite myself I began to like the man. “The devil can cite scripture to suit him,” I countered.

“E’en a Protestant must recognise that I am not the devil,” he said. “But enough banter – I will try to intercede for thee. ’Twill doubtless do no good, but I shall try.”

He led me to the base of the church steeple, where he pulled the sally of a huge cord and rang the bell thrice. Then we walked back to the nave to witness the chimes’ result.

In a quarter hour, the villagers began to straggle in past the guards, looking warily at me. They reluctantly filled the pews and awaited the reason for their summons. All looked in need of a good meal, and I began to see why they had resorted to coney-catching.

Father Twomey, deciding as many had arrived as could reasonably be expected, spoke to them in their ancient, liquid tongue. He indicated me once, and gestured in the direction of Iveragh House twice. His congregation remained surly and silent.

Finally, he asked them what was apparently a question, which I had to presume involved the return of the pilfered animals, and waited for a response.

There was, of course, none. The livestock had probably already been eaten, their bones e’en now bubbling in stobhach pots.

The priest looked at me as if to say, “what did thou expect?” I strode down the aisle, hand on the hilt of my sword and my spurs a-jingle, trying to look fierce. But there was nought I could do within the sanctuary of the church. Yet I could not return to my uncle without having ta’en some kind of punitive acture.

I turned back to Twomey. “Kindly tell them,” I said, “the village will be burned if they do not hand over the culprits.”

He did so. We waited, but again there came no response. Now I had no choice but to follow through with my threat or appear weak.

I thanked the priest, since the man had done his best on my behalf, and walked outside. “Burn the village,” I told my men.

The villagers watched as pitch-covered torches set fire to the thatched roofs, and the smoke from their shabby dwellings darkened the sky. It was an apocalyptic scene, and ’twas of my doing. How dost thou like this, father? I asked silently. Is this masterful enow for ye?

Resistance was done, as was the village.

I was ashamed of my order, though far less so than had I killed the villagers in reprisal. This was the purview of my duties, it appeared – to use sinew and steel against starving paupers. ’Twas not fair, to be sure, but life was not fair. Breaking one’s back on a farm for one’s whole life was not fair, getting press-ganged into the navy was not fair, dying of smallpox was not fair. All the options in the year of our Lord 1588 wast unfair.

That is what I told myself that night, when I tried to sleep.