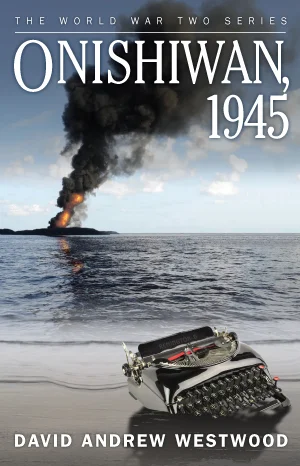

ONISHIWAN, 1945

Book VIII of the World War Two Series

Fiction: war/adventure/historical romance

Too old for the draft, Gil Rossiter spends his days in a basement of a Seattle newspaper typesetting articles about the war. His wife, a Japanese American, is incarcerated with her family in a Wyoming relocation center, her ethnicity the reason for his lack of advancement to reporter.

Meanwhile, Ray Ingersoll has been sent back Stateside for sentencing after shooting Japanese prisoners on Iwo Jima. Because he has an otherwise exemplary record, the authorities decide to assign him guard duty at the same internment camp. But Ray has been damaged more than just physically by the fighting, and he brings his hatred of the enemy to his new job.

When one of the paper’s combat correspondents is killed, Gil is offered the chance to finally write for the paper, but on what will become the arena for the last battle of WWII, the Japanese-held island of Okinawa.

Gil flies out, and follows a unit of Marines around the island until they are stopped at the hideous battle for the south. He watches as one after another of his new colleagues is killed. But there is a larger destiny in store for Gil, one that affects his wife back home.

Battle of Okinawa Facts

The Battle of Okinawa, codenamed Operation Iceberg, lasted from 1 April until mid-June 1945. The Allies planned to use Okinawa as a base for Operation Downfall, the invasion of the Japanese mainland. Four divisions of the U.S. 10th Army and two Marine divisions fought on the island, while another Marine division remained as an amphibious reserve and was never brought ashore.

By the end of the intense ten weeks, Japan had lost over 100,000 troops killed or captured, and the Allies had suffered more than 50,000 casualties of all kinds. 150,000 local civilians (one-third of the population) had been killed, and many more were wounded or committed suicide.

The controversial dropping of two atomic bombs on Japan forced its government into submission, and meant the invasion of its home islands was no longer necessary to end the war.

Sample chapter: © David Andrew Westwood 2012, all rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced without written permission from the author.

Chapter 10: April 1945

East China Sea, off Okinawa.

Gil’s ignorance of the strange entity called a Landing Ship, Tank became all too clear to him as his lurched toward the coast of Okinawa. LST 814 was a floating steel bucket, 21,000 tons and the length of the inevitable reporter’s yardstick, the football field. It superstructure sat far back on its hull, like an oil tanker, so that the front two-thirds could be used for cargo. Guns fore and aft, and huge bow doors that he had heard would accommodate any Allied vehicle, the LST was just one of hundreds pointed toward the Ryukyus. On this trip, 814 was carrying eighteen Sherman tanks and 160 men.

They crossed the tail of a typhoon, and the ship heaved like a dying animal as it hacked through three- and four-story waves. For a hideous hour, Gil despaired of ever again inhabiting a world where up stayed up and bulkheads stayed plumb. He could see the long hull flex, and waited for its rivets to pop. He watched the Shermans straining against their chains, and waited for them to break loose and crush everyone.

He was distracted from his imaginings by his queasy stomach, and soon was staring instead at its contents flowing into the Pacific. Greasy pork chops — the last meal before battle. No, this was definitely not the Bainbridge Island ferry. But the Navy and Marine personnel around him continued their business as if nothing was out of the ordinary, and he felt foolish and overanxious; a landlubber.

Eventually the East China Sea became comparatively calm, and they approached their destination. Religious services and crap games suddenly became equally popular. Land birds overhead and an indistinct strip of brown on the horizon showed they were nearing Okinawa.

Though he tried for an audience, Gil was not able to interview the Captain, but he did corner a Lieutenant j.g. Killian on the bridge at dawn. The sunrise, a red ball behind him, added a somber and unnerving backdrop to the man. They were entering, after all, the Land of the Rising Sun.

“What’s the plan, Lieutenant?” Gil asked, clutching his notebook and pen.

“This is our second Task Force. On L-Day we landed the 1st and 6th Marine divisions, and their orders were to take the center and north of the island. They already took care of the middle, now I hear they’re mostly up top. Two Army divisions have been landed, the 7th and 96th Infantry, and they’re to take the south. There’s a bunch of Seabees, plus a couple more divisions of Marines in reserve offshore. The British Navy is there, too, for added protection, at least for now. Though since the Japs lost the Yamato just north of here a few weeks ago I doubt their navy will show its face.”

Gil stared at his notebook, trying to calculate. “Uh … how many men in a division?” Killian was taken aback. “You’re a war correspondent and you don’t know that? How long have you been doing this?”

“A week.”

“Oh. Well, there’s ten to fifteen thousand men in a division, about five hundred in a battalion.”

“So there are roughly … 250,000 American troops now on Okinawa?”

“That sounds about right.”

“And what’s your prediction of the outcome of Operation Iceberg?”

“We’ll clean ’em off. But the capture of the other Jap islands — Tarawa, Guadalcanal, Tinian, Iwo Jima — was very costly for us. I doubt this’ll be any easier. The battleships have been shelling targets for days, but the Japs have had plenty of time to dig in.”

Gil scribbled in his own personal shorthand. “And where will LST 814 be during all this?”

Killian looked at the horizon. “Our nickname may be ‘Large Stationary Target,’ but we don’t hang around. And now, if you’ll excuse me, Captain, I have duties.”

Gil turned from the receding figure to the distant line of dark coast. Nothing could be seen of war on the land, but the ocean around seethed with ships and boats — including the USS Missouri and the huge aircraft carrier USS Lexington — bringing war to shore. Regular booms followed billows of orange from Missouri’s 16-inch guns as she pounded the island, over and over again. The huge shells hurtled off into the distance, exploding somewhere out of sight. Rockets burst from racks in screaming sets and followed. It was hard to believe anything could survive that pounding.

A Catalina flying boat circled around their crowded mast, and a few specks of Navy planes were scouting the horizon.

Gil guessed he had an hour or two at most to write and send a story from the radio room of the LST, and he found a quiet corner on deck to whip his notes into some kind of interesting piece for Semley.

TASK FORCE NEARS OKINAWA BY GIL ROSSITER, SEATTLE SEARCHLIGHT.

OFF OKINAWA, APRIL 20 -- THE EAST CHINA SEA BRISTLES WITH FLOATING ARMAMENT AS OUR DESTINATION, DECEPTIVELY PEACEFUL, LOOMS LARGER IN THE SUNRISE. BUT WITH A QUARTER MILLION MEN OF THE MARINE CORPS AND THE ARMY, OKINAWA WON’T BE UNDER THE RISING SUN FOR MUCH LONGER. SINCE LANDING ON L-DAY, APRIL 1ST, OUR FORCES HAVE BISECTED THE ISLAND, AND NOW FOUR DIVISIONS OF MARINES ARE TAKING THE TOP OF OKINAWA, TWO ARMY DIVISIONS THE SOUTH.

LIEUTENANT J.G. LEE KILLIAN, OF BRANSON, MISS., IS LOOKING FORWARD TO OFFLOADING HIS BATCH OF MARINES SO THAT HIS “LST” CAN RETURN TO THE RELATIVE SAFETY OF THE OPEN SEA AND ANOTHER TASK FORCE. ONCE ON THE ISLAND, THE…

The squawk of a klaxon made him drop his pad and pencil, and men appeared from every direction, swarming to the guns. A submarine? No, they were looking up. Gil stood, unsure where best to take shelter. He wished, fervently, that he had discussed this eventuality with someone who had some experience of it, but it was too late now.

They were close to the Missouri, the huge battleship towering above them, close enough to hear the thump and hiss as its seaplane was launched, close enough to hear the bugler over its PA system. Antiaircraft gun emplacements swung around, their barrels tilting up. An attack from the air, then. The LST started to swing away, beginning to zigzag as it avoided these big targets. Gil crouched behind the bridge superstructure and scanned the sky. There — in the distance, high — specks he had assumed were American. The air was abruptly shattered with the ackackack of antiaircraft guns, and black puffs began to fill the sky, crisscrossed by white streaks of tracer.

814 shuddered as larger guns joined in, blamblamblam. One of the specks — two — began to smoke, and one twirled down toward the ocean. The other came nearer, still on course despite flaming like a meteor. Loudspeakers were issuing orders, but Gil was deafened by the guns behind him and could not make out the words. Men were charging to and fro, and he was forced against the rear of a tank, out of their way. The shapes were close enough to make out now: the radial engines and silver, some dark green, bodies of Zeros. Flashes came from their wings, and the deck, tanks and superstructure of the ship were raked with bullets. Other, unfamiliar planes appeared. They looked like trainers — older, slower. Before he crouched under the Sherman he glimpsed a twin-engined Betty, low, just above the wavetops. He should be taking cover, but he couldn’t tear his eyes away from the aircraft. One was shot down into the waves, cartwheeling, another exploded in the air and flaming pieces continued to descend on its original trajectory, falling just short of the ship. Belatedly, with dawning horror, Gil understood what the Japanese planes were doing. They were not trying to live to fight another day; they were on one-way trips — suicide missions. Their entire plane was a bomb. They were Kamikazes.

The flaming Zero came closer and closer, until Gil stared, mesmerized, convinced it was heading for him personally. At the last moment it lost its lift and plowed into the ocean just starboard of the bow, exploding in a double burst as its explosives and then its gas tanks ignited. It was so close to the LST that part of the vessel’s hull bent in from the explosion, shoving men away who were sheltering against it. Shards of plane sprayed outward in an orange ball of fire that expanded and roiled upward, replaced by thick black smoke and cracks of exploding shells.

The LST’s deck heeled over as it changed course again. Another Zero smashed into the deck of a ship a half-mile away, throwing up a huge gout of flame. Gil gagged on the taste and smell of cordite, aviation fuel, and smoke. Men rushed in front of him, some crimson with injury. Others lay dead, their blood sloshing around the deck with the bilge.

But the attack was over, at least temporarily, and the smudged sky was clear of aircraft. Gil hurriedly finished his story with shaking hands; his typewriter perched precariously on a Sherman.

ONCE ON THE ISLAND, THE MARINES WILL MOVE NORTH TO SUPPORT THOSE DIVISIONS ALREADY FIGHTING THERE. NOW THEY HAVE COME THIS FAR, THE MEN ARE EAGER TO COME FACE TO FACE WITH THE JAPANESE, TO TEST THEIR TRAINING AND THEMSELVES IN THE HEAT OF BATTLE.

MEANWHILE THE HUNDREDS OF SHIPS OFFSHORE ARE BATTERED BY SUICIDAL KAMIKAZE PILOTS, WHO BURROW INTO THE CURTAIN OF ANTIAIRCRAFT SHELLS HURLED AT THEM TO TRY TO DEMOLISH THE FLEET AND DEMORALIZE ITS SAILORS.

THE ISLAND OF OKINAWA IS NOT GIVING UP EASILY.

He quickly found the radio operator and handed his sheets to him. The man nodded and yelled, over the din, “After the censor, OK?”

LST 814 churned on, through the surf onto the sand, and opened its doors. The men charged off, prepared for resistance that did not materialize, and the tanks started up and followed, churning across the beach in clouds of exhaust.

Gil watched for a while and then, remembering he was one of the men, followed the rest of the Marines while juggling his M1 and his other burdens.

“I recognize a typewriter case when I see one,” said a voice on Gil’s right, as he waded ashore through the surf. “Welcome to writin’ about hell.”

Gil turned to see a wiry, balding man from another landing craft trudging along beside him, also carrying a typewriter. “Been at this for a while?” Gil asked him.

“You could say that. France, Italy, and now the Pacific. Kinda forgetting what home looks like.”

“Where is home?”

“Oh, I’ve lived in lotsa places. Kinda missin’ Albuquerque right now.”

“I’m Washington State. Seattle.”

They followed the rest of the men over the lumpy sand.

“Ah, love the Northwest. You with the Searchlight?”

“I am. You?”

“Oh, Scripps-Howard, and my stuff gets syndicated, so I’m all over the map. Stars and Stripes, too. Say, this your first time in action?”

“Yessir.”

“Well, friend, if you don’t mind some advice from an old hand, keep your head down. Mr. Jap leaves snipers even in the areas that have been cleaned. It’s a dirty business always, but ’specially out here.”

“I’ll do that. Thanks.”

“Well,” the man held out his hand, “I’m off to meet some fellas up front. You take care. ’Spect we’ll meet again when we radio in our stories.”

“Yeah. All the best.”

Gil trudged between the gouged and headless palms, squinting across the muddy estuary of a river, where the rest of his company was heading. This didn’t seem too bad. No fighting here on the bay. Perhaps the ships and the planes really had softened it up for the Marines, like they were supposed to.

As he reached the group of men he’d shipped with from Ulithi, pooling around a group of trucks, a Sergeant turned to him.

“What did Ernie have to say?”

“Who?”

“You was talkin’ to Ernie Pyle.”

Pyle? Gil felt as if he’d already managed to miss one of the best opportunities in his short reporting career — to interview the great writer Ernie Pyle, pal of all the leathernecks, swabbies and dogfaces in the war. He could have learned a lot just then; instead all he had come away with was to keep his head down. Oh well, they would run into each other again, like Pyle had said. They had to submit their stories either from headquarters or from a ship; so all the correspondents must cross paths then.

“All aboard who’s comin’ aboard,” the sergeant called from the back of a truck.

Gil climbed in and took out his notebook and pencil. He studied the man. He was short and square-jawed, his proportions looking as if something heavy had fallen on him. “What’s your name, sergeant?”

“Eustace. Eustace Posen. No jokes about it, or I’ll lose you in the jungle.”

“Where are you from?”

“Tucson.” He turned away to address the other occupants of the truck. “Now listen up, you guys — this is Kadena. We’re headin’ north to where the first Marines that landed on L-Day need help. Place called the Motobu Peninsula. Just ’cause there weren’t no resistance on the beach don’t mean we ain’t gonna see any. I hear it’s rough up there. Those of you who were on the other islands know what I mean. You new guys watch what the old hands do — trainin’s over.”

Once he was sure the sergeant had finished, Gil said, “What d’you think of this war, Eustace?”

Posen winced. “Call me Eus, for Pete’s sake. I think it stinks. Lost a lot of good buddies on the other islands. Now it’s payback time. Gonna get as many of the little yellow bastards as I can.” The truck lurched on, away from the beach, along with the halftracks and amtracs and tanks. Five P-45s flew low overhead. “Only sorry there ain’t any on the beach, so’s I kin get started.”

“What about you, uh…?” Gil turned to the young, fresh-faced private next to him. The man was slim but well muscled, his hair slicked back.

“Angel.”

“Angel?”

“Sure. It’s Spanish. Ahnhel. I’m from El Paso—”

“He don’ plan on becomin’ an angel, though,” interjected Eus. “Not yet.”

“—Gonna get this over wit’, an’ get onto Japan. Wipe ’em out.”

“This is one o’ the gentlemen o’ the press,” Eus explained to the men in the truck, “He’ll be talkin’ to youse about the war. Now, you can talk to him, but kindly finish talkin’ to the Japs first.”

Gil and his group of Marines lurched northeast along the narrow Okinawan roads, uneasy. Then they stopped and left the truck, continuing on foot.

“Don’t like it,” Eus kept saying. “Look smart. Stay alert. Don’ bunch up.” He turned to Gil. “You keep to the back, Scoop.”

Gil, after a moment’s confusion, understood that ‘Scoop’ referred to him, or more probably any reporter.

They walked warily past a treadless Japanese tank outside an abandoned camp. They crept cautiously through, reluctant to touch the ant-covered meals, the file drawers, the ammunition boxes.

“Watch out for booby traps. Watch out for snipers,” Angel told Gil.

Amid ruins they glimpsed their first native Okinawans, picking through the debris of their homes, holding emaciated children, and staring warily at the Americans. Many had blackened teeth, Gil presumed from eating sugar cane.

“Okies bin shelterin’ the Japs,” Eus said. “Watch out for them also. I hear some o’ the Japs dressin’ up like they’s civilians.”

“Do they consider themselves Japanese?” Gil asked.

The sergeant shrugged. “Okinawa’s technically part o’ Japan. But the Japs don’ like ’em much. Second-class citizens, kinda.”

Still they saw no live enemy. Gil was so exhausted from nervous tension that he could hardly eat his dinner C-rations. “When can I radio my story in?” he asked Posen.

“Tomorrow night we’ll be setting up an HQ. Then you can have a word with the brass about priorities on the radio. Middle o’ the night, I’d guess.”

“So, Eus,” Gil said, remembering his duties to gather information and opinions, “What d’you think of your orders to take Okinawa?”

The sergeant grunted. “I’m a Marine. I go where my President sends me.” He glanced back at his companions. “But not where his wife says.”

“His wife?” Gil couldn’t think of Mrs. Truman’s name, then realized she was not who Eus meant. “Eleanor?”

“You didn’ hear what our illustrious First Lady thinks about us Marines? She thinks all of us fightin’ in the Pacific should be kept on the west coast for six months when we get back, ’fore we’re allowed back into contact wit’ decent American womanhood.”

There were harsh laughs from the other men.

* * *

As he tried to get comfortable under his blanket and poncho, Gil wondered how Pyle and the other reporters dealt with this life, day after day, month after month. He supposed they had no choice. They either got used to it or got sent home in a bag. His sleep, when it came, was shallow and chopped into unsatisfying shards by flashes of light, men talking, truck gears crunching, and the rumble of tanks moving up. His imagination, once thought of as an enviable, valuable talent, now showed itself to be a traitorous source of vivid images of charges of crazed Japanese soldiers, sprays of hot lead searing through his body, land mines exploding between his legs. The most unnerving, recurring vision was of a bayonet lunging at him, sharp.

His lonely Seattle house seemed now, from this distance, a haven of safety, his boring job a soft and easy way of making a living. He had always respected soldiers, but now he looked on their uncomplaining bravery with an awe verging on idolatry. The values of society were inverted, he saw in a moment of insomniac clarity — politicians, statesmen, captains of industry were at the bottom level, soldiers at the top.

And the openness. He had never been agoraphobic, but the lack of a roof — ever — was unnerving. That was one of the things basic training gave you, he supposed, an ability to give up the entire concept of shelter. He felt like a snail with its shell peeled off.

By way of keeping his mind occupied on something that could distract him from thoughts of imminent death, Gil wrote his next story in his mind.

FIGHT CONTINUES ON OKINAWA. BY GILBERT ROSSITER, SEATTLE SEARCHLIGHT.

OKINAWA, APRIL 21 -- THE NIGHT IS UNNATURALLY QUIET. EQUIPMENT RUMBLES BY, BUT AS YET THIS GROUP OF MARINES HAS NOTHING AND NO ONE TO ATTACK. EITHER THE JAPANESE HAVE BEEN DECIMATED BY THE FIRST WAVE OF LEATHERNECKS, PLUS THE NAVAL SHELLING AND AIR ATTACKS, OR THEY’RE OUT THERE, WAITING.

SERGEANT EUSTACE POSEN OF TUCSON THINKS THAT TOMORROW WILL SHOW US THE TRUTH ABOUT THE ISLAND OF OKINAWA, THE CLOSEST YET U.S. TROOPS HAVE GOTTEN TO THE ENEMY MAINLAND. PRIVATE ANGEL OTRILLO OF EL PASO JUST WANTS ENCHILADAS AGAIN, BUT FOR NOW HAS TO SETTLE FOR RATIONS FROM A CAN. WHEN THE SUN COMES UP IT WILL SHOW A DECEPTIVELY PEACEFUL TROPICAL ISLAND, THIS CENTRAL PART LOOKING A LOT LIKE FLORIDA.

THE FEW NATIVES WE HAVE SEEN SO FAR LOOK FRIGHTENED, AND STAY CLEAR OF THE AMERICAN TROOPS. THE WAY THEY HIDE THEIR CHILDREN SHOWS THAT THEY HAVE BEEN TOLD THAT WE ARE NOT LIBERATORS, BUT PSYCHOTIC THUGS.

His body wanted to sleep, but his mind refused. Old, formerly buried memories swam to the surface and floated before his eyes in the dark. One in particular.

He was with his father on their one hunting trip to British Columbia. He hadn’t wanted to go, but his father had dismissed his feelings as childish cold feet. It would be a great experience for them to hunt together, he said, an adventure. It was time for Gil to grow up, to be a man. His own father had taken him hunting when he was a boy, and now he intended to pass down the lesson to the next generation of Rossiter men. Besides, he explained, the deer needed culling, or they would overmultiply, and some would starve.

Gil had enjoyed the camping part, though it was cold. Huddled around the fire with bratwurst and beer, surrounded by the sentinel pines — it was exciting and primitive. Bitter, hot coffee in the morning while shivering and waiting for the sunlight to reach the campsite, the preparing of the rifles, all made him feel accepted into adulthood.

It was a bright, crisp day. His father shot a doe early and strapped it to the hood of the car, and full of expansive triumph had led his son deeper into the forest for his own chance. Gil had wanted to turn back, one killing being more than enough for him, but his dad insisted they continue. Finally, in a sun-dappled clearing they came across a family of black-tailed deer.

His father had mimed raising his Savage 99, urging him to shoot. Gil had reluctantly put the stock to his shoulder and sighted on a young buck, a beautiful creature, its ears alert and twitching, its big eyes gleaming in the sunlight. This was, he saw clearly, one of God’s most graceful creations, all the more exquisite in its natural element and not a zoo. Who were Homo sapiens to consider themselves the pinnacle of evolution when animals like this existed? It was a privilege to even witness its living presence. To think of taking its vitality away—

Intentionally, he aimed just to the left of its head in order to miss, and squeezed the trigger. As he did so, the group, alerted by some subtle clue to the humans’ presence, tensed and sprang. The buck moved into Gil’s shot. Part of its neck was blown away, and it careened off into the trees unbalanced, badly hurt.

His father had been furious. A clean kill, he always stressed, a clean kill. Now they would have to follow the deer and put it out of its misery.

Gil wanted to be put out of his own misery, as he and his father followed the vivid blood trail across the forest floor. He wanted to be anywhere else, anyone else’s son. Just not here, and his.

All too soon they came across the injured animal lying panting in a glade, abandoned by its clan.

“Go on, then,” his father had told him, “Finish it off.”

Gil had looked into the terror-wide eyes of the deer and raised his rifle. There was no way out of this. He sighted at its heaving breast, where he could see its heart beating, and fired.

He shook himself awake into a surreal nightscape of blurred shapes, muffled conversations, grumbling vehicles. What had possessed him to volunteer for this? Who was he trying to kid? He didn’t even like the dark, and here he was by choice in the midst, the very eye, of a war.